01 May Anxiety, Isolation and Loneliness

Feelings of anxiety, loneliness and isolation have been a common experience for many the two-and-a-bit years since the COVID-19 pandemic began. During Melbourne’s rolling lockdowns, you didn’t see friends or family the way you might have been used to. Most likely, you missed colleagues from work and peers from school or university. Maybe you even missed your regular barista on your usual commute.

At some point in the COVID-19 lockdowns, you likely felt lonely. Most of us did.

In small doses, loneliness can be like hunger or thirst – a healthy signal that you are missing something and to seek out what you need. But in the long-term, loneliness can be harmful to mental and physical health, like other forms of stress, increasing the risk of depression, anxiety and substance abuse.

Here’s what neuroscientists think is happening in your brain when you experience prolonged loneliness:

The human brain has evolved to seek safety in numbers, so it registers loneliness as a danger. The centers of the brain that monitor for threat, kick into overdrive and trigger a release of stress hormones. These feelings of danger can then subconsciously become linked with other people, causing you to view them more as potential threats and less as friends, remedies for your loneliness.

This particularly relevant in the present, as pandemic restrictions are lifted and we have exited social isolation. As we regain some semblance of normal, we may experience post-lockdown anxieties.

Readjusting to life after lockdown can be stressful! It can lead to uncomfortable experiences like worry about the pace of the restriction changes, fear about the future or feeling generally overwhelmed. It may seem easy to control this by avoiding the anxiety producing situation or isolating yourself to get temporary relief from the anxiety. You get immediate gratification and relief by avoiding your worst fears!

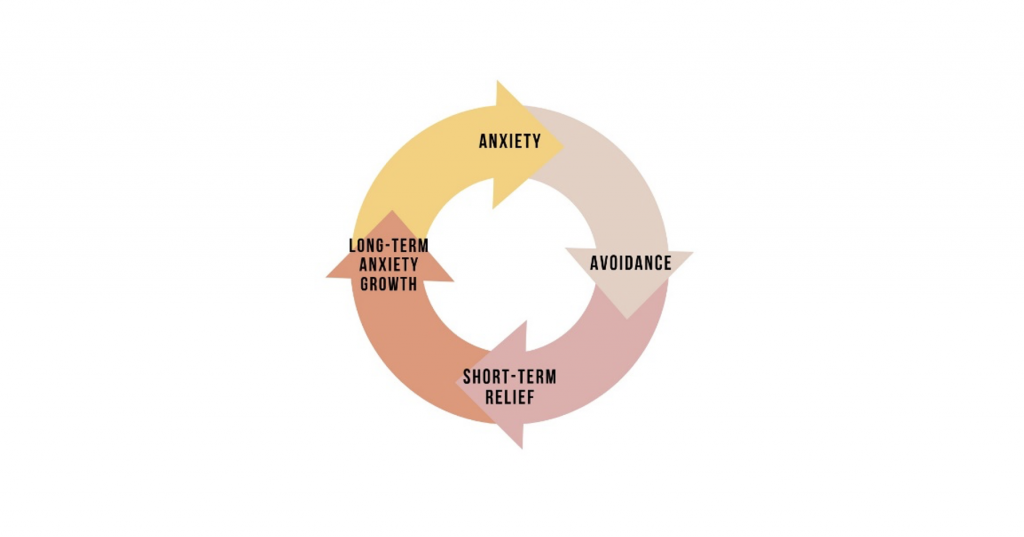

But avoiding situations that provoke a sense of anxiety actually increases anxiety in the long-run. When you avoid anxiety provoking situations, you decrease your ability to tolerate distress, build negative psychological associations and end up in a vicious cycle of anxiety (See below)

Credit: The Counselling Collective, 2019

Luckily, there are ways to cope with the anxiety of “getting back to normal”. It’s important to be patient with yourself and your feelings and not to compare how you process these changes to how others do, as we’ve all responded to the pandemic differently. It is also important to recognise that even positive change can lead to anxiety and it can take time to readjust to things we’ve not done for a while. Here are some tips:

-

-

- Go at your own pace: It may be tempting to make lots of plans and agree to every social invitation, but there’s no need to rush. Do what is comfortable and build up as your confidence returns.

- Start small: Start with small and manageable goals (this may look like a coffee outside with a friend or a snack at a café with outside seating). Make sure the goals are important to you and feel achievable.

- Make time to relax: Being able to see more of our friends and family again is exciting. But it can be a lot to take in too, so scheduling time for yourself to relax is important. Many people find it helpful to spend time outside in a park or garden reconnecting with nature.

- Tell someone how you feel: It’s not unusual to feel alone or isolated when we’re anxious. But chances are, someone we know is feeling the same way we are. Opening up to a person can be really helpful; whether it’s a family member, friend, GP, mental health professional or an organization’s online forum or helpline.

-

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.